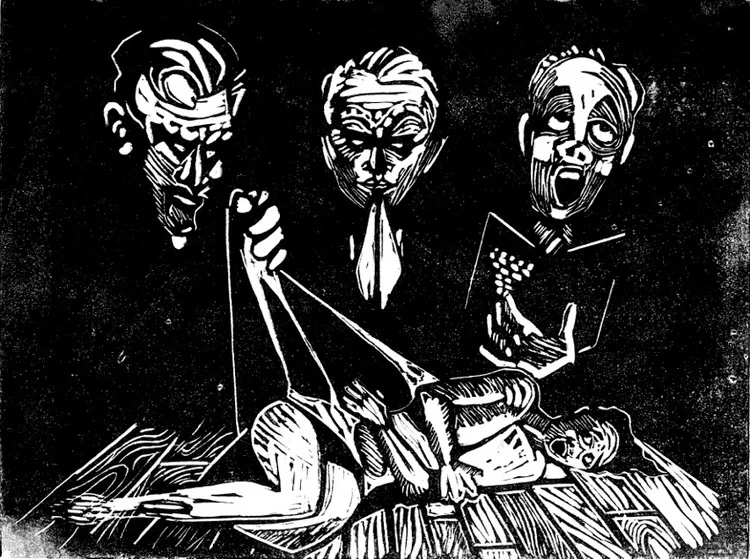

© 2015 Carl Wilson, "God is Love"

The Atrocity of SunSets:

The Death of Childhood in Michigan

A personal look at the imprisonment of juveniles in Michigan, a state that sentences juveniles to life without parole at a higher rate than any other state or country in the world.

//chris dankovich

I have suffered the atrocity of sunsets.

Scorched to the root

My red filaments burn and stand, a hand of wires.

— Sylvia Plath, "Elm"

***************

There is a history of juvenile incarceration in my family going back generations, though it’s not the standard story you hear from most career criminals. My great-grandfather Jan (John) Dancovic, years before coming to America, was conscripted to fight for his birth country, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in World War I. Old enough to go to war there but still too young to drink or smoke here at the time, he was shot and left for dead, and was eventually placed in an Italian prisoner-of-war camp. His son, my grandfather John Jr., was born a few years after the war. When Grandpa John was 14 and old enough to start providing for his family, his father sent him to work at the steel-mill in the Detroit area. A standard physical revealed that he had tuberculosis, and he was sent against his will to Maybury Sanitorium (sanitarium for mental disease, sanitorium for physical ones) in Battle Creek, Michigan. He used his incarceration productively — he ran the sanitorium newspaper with future comedian Dick Martin, finished his education, and got a scholarship to a university upon release, eventually earning a job as an engineer at General Motors. My father Jim managed to break this unfortunate tradition (though he did once work at a juvenile detention facility). With help from my grandfather, he went to school and became a chiropractor, one of the most successful in Michigan, taking care of the rich (and occasionally famous) in the metro-Detroit area. But this isn't an American success story. This is more of an American failure story. Every day across the nation, children — 13, 14, 15, 16 years old — are put into adult prisons. I'm one of them.

****************

I started my incarceration at 15 years old in Oakland County Children's Village in Michigan, a secure juvenile detention and holding facility. The bathrooms there were cleaned thoroughly every day, but the rest was cleaned only occasionally, and so the only parts of the facility that didn't smell like urine were the bathrooms themselves. Most of the kids there were between 13 and 16, some younger, a few older. They stole cars, sold drugs, got caught having sex with their girlfriends (or occasionally boyfriends), who were often the same age as they were, making it statutory rape. Some were incorrigible, some were disrespectful, some gave up their snack to the new kids to help them feel more comfortable. The staff was professional, sometimes strict. They were usually willing to offer advice, but the “residents,” like most kids, sought out their guides and role models in their peers. Each “pod” of resident children was generally kind and fairly gentle-worded to each other, though it would only take one bad apple to turn them into rioters.

There was a tension in these kids: most had seen violence, many had experienced it. Most were prescribed some sort of medication; many were doped up to the point of barely functioning. Most regularly did drugs before going there; many started their drug abuse with the drugs they were prescribed. We would sit in the corners of the pods, at the picnic tables with the laminate chessboards on top, and trade tips on what to say to get the psychiatrist to prescribe us whatever we wanted, where to score good weed, how to steal a car, where the children’s shelters were if we were being abused at home. There was one kid, Dmitry (11 years old), who would hide under those tables and cry whenever the staff or other residents got angry at him. He wouldn’t come out for anything except, occasionally, if I talked to him. He was in there for molesting someone or something — a biological or step-brother, sister, a neighbor, the dog — as he had a Criminal Sexual Conduct (CSC) charge. He was doped up on the highest level of Adderall (multiple doses of thirty milligrams) and the anti-psychotic Seroquel (a thousand milligrams just in the morning) I had or have ever heard of.

Once sentenced as an adult, at 16, to adult state prison, I couldn't stay in juvenile detention, and I was taken to the county jail. The next week, I was placed in the state prison intake center in Jackson, MI. The hometown of the Republican Party in the 1800s when the party began as the anti-slavery party, [1] Jackson’s economy is now completely centered around its prison system, once the largest in the world. I was kept in a separate, caged-off area in one of the massive cell blocks because I was the only under-17 juvenile there, though having been charged as an adult, I was no longer a legal juvenile — now I was a “youthful” adult. The prison looked just like the movies, a lot like the prison on Alcatraz where I visited on family vacation three years earlier. Rows and rows of steel-bar enclosed cells, tiers stacked upon each other. The porter who would clean the floor in front of my cell every few days, the only prisoner I really had any contact with, offered me cigarettes because he felt bad that I couldn’t buy tobacco. He said that it was the only thing that made life bearable in there.

I was transferred to the next prison in two weeks, much shorter than the normal two to three months, as I had to be escorted everywhere I went because I was too young for general population, which I’m sure grew tiresome for more than just myself. Seven months after I turned 16 years old I arrived at Thumb Correctional Facility’s “Youthful Offenders” side, Michigan’s only prison for adult prisoners ages 13 to 18 (though some stay into their early 20s). I joined some 400 other “youthful” adults in the two units reserved for us, set apart by some fencing and a building we shared with 800 “adult” adult prisoners.

****************

A state whose forbearers eliminated the death penalty due to the moving temperance speeches and last words delivered by a man who killed his lover in a drunken rage and remorsefully walked to the gallows, [2] Michigan has a history of treating those of its citizens who often cannot legally drive a car, smoke, drink, or consent to the touch of another excessively harsh — the harshest, in fact, in the entire world.

While the United States of America only officially stopped executing juveniles in 2005, [3] it had been many, many years since any juvenile was actually executed. Instead, states have taken to sentencing juveniles to life in prison without any possibility of parole or early release — sentencing them to live out the rest of their lifespans (the average lifespan for a juvenile serving life is 52 years) [4] and die in prison.

Michigan took the lead, sentencing its juveniles to life without parole at a higher rate than any other state or country in the world. Before the United States Supreme Court banned the practice in 2012, Michigan mandated that any juvenile found guilty of any amount of participation in a premeditated murder (even if it was a plan that wasn’t carried out) or a death caused by anyone during the commission of any felony be sentenced to the state’s maximum sentence. [5] Hence, Kevin Boyd, who at 16 gave his estranged mother the keys to his father's house, which she and her lover used to rob and murder his father, receives the same penalty as John Norman Collins, a serial killer who cruised Michigan college campuses raping and murdering students. Cedric King, who at 14 accompanied his adult older brother to the apartment of a man who was subsequently shot in the leg by the older brother will die in prison (for his charge of conspiring to kill the man, even though the man survived), while Charles Manson is currently eligible for parole. Keith Maxey, who at 16 was shot multiple times when he went unarmed with a few friends to buy some marijuana and a shootout occurred between one of the group and the drug dealer, will spend the rest of his life incarcerated, while Gavrilo Princip, who started World War I by assassinating the Archduke and other royal members of my great-grandfather’s homeland as part of a terrorist organization, got sentenced to 25 years. The early-20th Century aggressive dictatorship held that it would not condemn a juvenile to die in its prisons by any means. [6] [7]

****************

About half of the juveniles at Thumb Correctional Facility's Youthful Side are sentenced under the Holmes Youthful Trainee Act (HYTA). [8] HYTA’s are youth from 13 to 21 who are sentenced to adult prison for up to three years, after which they are released and their records expunged. Many of those with less serious offenses, who at one time would have been sent to a juvenile detention and rehabilitation facility, end up with HYTA. They take GED classes and one of two vocational classes when there's space available, taught by adults like myself who teach, tutor, and review lessons with them under the supervision of a teacher for one to two hours a day. They are locked in their cells — in what used to be maximum security units designed to hold some of the state’s most dangerous adult criminals — for most of the remainder of the day.

Most of the rest of the juveniles there (bearing the full legal adult burden of their mistakes) will be eligible for parole, though about a third won’t be until they have served more time in prison than they have already been alive. Only a small percentage of these youth are serving life without the possibility of parole. But there is Christopher Bailey, who has severe cerebral palsy and can barely walk even with the aid of crutches, sentenced to a minimum of 10 years in prison at age 14. “Sharkboy” Walker, autistic and with a diagnosed emotional and intellectual age of seven, received a sentence of 12 years, also at 14. Juvenile adult prisoners are disproportionately of color, disproportionately poor, disproportionately missing one or both parents (who have full legal decision-making authority over your defense) from their lives, disproportionately mentally ill. [9] Once they leave Thumb Correctional Facility for another prison, they are at a disproportionate risk of sexual predation and rape. [10]

****************

I recently watched an episode of Law and Order: Special Victims Unit in which a teenage boy was accused of a heinous crime. Detective Stabler, the archetypal hardened detective who plays by his own rules but also has a soft, compassionate side, makes it his mission to find out why the tragedy happened — what made the boy capable of such a thing. The other detectives in the unit debate the culpability of children and investigate leads that might mitigate the boy’s responsibility. The unit psychiatrist, soft-spoken but determined Dr. Hong, performs a forensic psychiatric evaluation on the boy right there in the station, seeking out what may have happened to the child … with the child … during the crime … eventually discovering the boy was far from an adult, far from a sociopath, far from malicious. They guided the boy through the criminal justice system, eventually convincing the judge to have him treated instead of punished.

When you’re a child and are charged as an adult with an adult crime (there are many crimes other than murder that will make a 14-year-old a legal adult), the experience is far from the movies or a Law and Order episode. There are no safeguards for you. Justice will not seek to understand why the alleged offense occurred, what led up to it, the psychology, reasoning, or capacity of the child perpetrator. If anything, you’re considered more dangerous than an actual adult criminal because, “How could you be so young and still be capable?” But no one will go out of his or her way to find out that answer unless your parents, who, again, have full legal control over your defense, hire a professional — but that assumes they know to, know how, have the money, care, and are there. No rehabilitation is sought for you. From the moment the prosecutor decides to charge you as an adult, the only option available to your future is straight, hard punishment and suffering. The only thing you can do is try, as a child, to argue against an adult well-versed in the law and whose many years of schooling and experience have gone into beating you, to convince him or her that you didn’t commit the crime or that you deserve less than everlasting damnation. Your only ally is your attorney, whom you did not hire and could not have, since you cannot legally sign a contract and have no legal right to possess your own money. 38% of lawyers representing juveniles that face a life without parole sentence in Michigan have been publicly sanctioned or disciplined by the Michigan Bar Association for egregious violations of ethical conduct (though in any given year, only about 0.3% of Michigan attorneys are reprimanded in such a way). [11]

****************

Most Michigan counties have some sort of juvenile detention facility like Children‘s Village, and the state itself runs a few that are designed to both treat and secure juvenile delinquents instead of directly punishing them. In the wake of predictions about child super-predators in the late 1980s and the reality of out-of-state school shootings in the 1990s, former Governor John Engler gutted funding for state juvenile facilities and mental institutions, dissolving most of these youth-serving establishments. The bankrupt mental institutions were, from the 1920s to the 1970s, considered some of the best and most innovative in the world. The physical plants of the properties and assets were liquidated as well, and emphasis was shifted to the more “cost-effective” outpatient and county treatments and programming. [12] These outpatient treatments and programming never really got off the ground, however, and the juveniles and mentally ill instead began being pushed into the state prison system, the only option left. While still cost-effective in the short-term, as a prisoner costs about half as much to house as do juveniles or the mentally ill who need treatment, prison sentences tend to be longer than those individuals’ treatment would have been. A juvenile sentenced to life without parole, for example, will cost an average of $2 million over his or her short lifespan. [13] The governor’s term also saw the implementation of the automatic waiver system, in which children 14 years old or older are automatically “waived” to adult court if even so much as charged with a serious crime, eliminating a judge's discretion to even possibly decide to try the juvenile in juvenile court. [14] Governor Engler is still hailed by many state Republicans as the state’s premier conservative for balancing the state budget. Much of this was accomplished by the sale of those institutions and by negotiating the sale of Michigan’s Great Lakes water rights to foreign governments and corporations in China and France.

Other states’ leaders have been more blunt in recent years about bestowing the responsibilities of adulthood on juveniles as young as eleven. Former Arkansas governor, presidential runner, and current Fox News Channel show host Mike Huckabee brags in his pre-presidential run autobiography about how, after a 13-year-old and his 11-year-old brother opened fire on an Arkansas middle school, he lobbied his state’s legislature to pass a bill that would have enabled preteens to be tried and sentenced as adults to life in prison.

****************

The rest of the world, except for America and Somalia, officially recognizes the difference between juveniles and adults in terms of ability to navigate their criminal justice systems and the juvenile‘s level of culpability regarding their responsibility for crimes they are found guilty of. [15] In America, the mantra repeated by lawmakers and prosecutors who advocate these harsh adult punishments for juveniles is “Adult Time for Adult Crimes.” [16] This was the title of a Heritage Foundation report, which argued that the United States could not be in violation of international human rights norms because the U.S. is the only nation that has refused to sign and ratify the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child, which mandates that

“(a) No child shall be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Neither capital punishment nor life imprisonment without the possibility of release shall be imposed for offenses committed by a person below eighteen years of age; (b) No child shall be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily. The arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.”

Actions do not determine chronology; years do. But in America, prosecutors determine whether a child is a child or an adult before they are actually found guilty of anything. Children are a class of people deprived of the rights of adults because they are deemed not responsible enough for their actions. Should they even so much as be accused of violating the law, however, they are given the full burden of those responsibilities while never having enjoyed any of the rights. Children, even those accused of the worst crimes, deserve basic civil rights and to be treated as more than second-class citizens. All those who bear the same burdens and punishments deserve the same rights, or they do not deserve the same burdens.

© 2015 Hartmut Austen, "Wonderer"

The vast majority of juveniles who come to prison, perhaps with problems, perhaps somewhat antisocial, come for making a mistake. There they are likely to be transformed by adult prison culture of criminal instruction, violence, and domination into something they weren’t before, something scary. And these children, the forsaken ones cast into the lion’s den for petty crimes, will be released not knowing how to pay taxes, having never held a job, without having finished high school. Perhaps the scariest aspect of the change in these juveniles is that it didn’t have to occur. But there are also many who, with guidance and opportunity, would grow up to become actual adults and assets to society. Impetuousness is usually outgrown. Young adults learn that their mothers, fathers, brothers, and older friends are not gods who must be obeyed — individuals whom, as juveniles, the youth often could not emotionally, intellectually, or sometimes even legally separate themselves from. This is how I came to prison, sentenced to 25 years after childishly rejecting my own insanity defense from one of the nation’s foremost experts, for taking the life of a parent who once tried to force me to have sex with her and beat me so bad I had to go to the hospital. [17] Hundreds of incarcerated youth will not get these opportunities, or even the opportunities that I’ve had. Many, should they somehow manage to sow and reap these positive traits in the emotional desert of prison, will never have the opportunity to prove to others the men and women they’ve become.

****************

Had my great-grandfather Jan stayed in his ethnic homeland instead of coming to America, and I had been born (along with the other juvenile offenders at the Thumb facility) in Slovakia or Hungary, childhood would have been a time to mature into an adult, no matter the mistakes of youth. Instead, for many, youth begins as a period of abuse and violence, only for them to be condemned to a never-ending future of abuse and violence. One of the principles that the United States and other liberal democracies around the world are founded on is the idea that those subject to the authority of a governing body must have the ability to have some say in the governing processes. Should a juvenile of any age, who has almost no legal control over his or her life, be held equally as responsible and treated and punished exactly the same as a fully autonomous adult when they violate (sometimes at the behest of those with authority over them) the laws of a legal system they know nothing about and have no say in?

What are your teenage years for? Are they to learn? To mature? To grow up? To become an adult? When exactly does one become an adult? At 13 you can be tried as an adult — at 14 you are often automatically so if charged with certain things. At 16 you can drive with many, many conditions, or become an emancipated minor (but there's the qualifier in the sentence — a minor still). You may be able to consent to sex with a lover. Before then you can never know the intimate touch of another, not legally. At 18 you can vote, smoke, buy a gun. You certainly are no longer called a minor. Most graduate high school. At 19 you are in the final stretch of that seven-year sentence of being a teenager. Are you an adult now? Is it automatic? If not, in those last few months, weeks, days, hours before your 20th birthday, do you become one? Can you feel the transformation, adulthood suddenly “there?” Or is it not a specific moment in time — and rather, a gradual process, a gauntlet, a crucible, an evolution of gained rights?

Where is childhood? It was there at Children's Village, in the cries that life was over after being sentenced to nine months in juvenile programming, in pills snorted to make the unbearable burden of youth pass quicker, in the childish faux attempts at escape by climbing the 15-foot inverted fence in broad daylight, inches from security staff. It was there in the sharing of cookies at snack time, in the thought that ingesting certain chemicals really could make the world a better place and the pain go away, in the belief that when we die, we come back as a blade of grass (to be cut down again?).

There is no childhood in state prisons. It is a place of men, not of boys — men who stand up for themselves, who fight for themselves, their honor, and their greed. Their advice — stand up straight, keep your head up, don‘t walk so fast, start doing pushups (“But I already do multiple sets of 75.” “You do? That can‘t be — you're so small”). Sometimes taunts from those who thought I couldn't or wouldn't do anything back. Sometimes sympathy — hands reached out to shake; kind words; writing on the underside of my sink (next to gang graffiti) that read, “God loves you” and “Everything gets better.” For thousands of children across America, it doesn't.

Footnotes:

[1] The Jackson, Michigan Historical Society.

[2] The New American Encyclopedia, Volume M. Published by Frolier, Inc., 1998.

[3] Roper v. Simmons 543 S.Ct. 569.

[4] "Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics 1985-2008," National Center for Juvenile Justice.

[5] Miller v. Alabama 132 S.Ct. 2455.

[6] Personal interviews conducted with Kevin Boyd, Cedric King, and Keith Maxey, along with review of certain respective court documents.

[7] The New American Encyclopedia, Volume P. Published by Grolier, Inc., 1998.

[8] Michigan Compiled Laws §799.81.

[9] Both personal experience and "Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics 1985-2008," National Center for Juvenile Justice.

[10] Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Act of 1974 (42 USC §5633).

[11] Basic Decency: Protecting the human rights of children, a pamphlet published by the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan, 2013.

[12] Waiting for Disaster, a documentary by Channel 7 ABC Action News Detroit, WXYZ, 2014.

[13] Second Chances: juveniles serving life without parole in Michigan prisons, a pamphlet published by the American Civil Liberties Union Juvenile Life without Parole Initiative, 2004.

[14] Michigan Compiled Laws §712A.2.

[15] International Convention on Civil and Political Rights and Concention of the Rights of the Child, United Nations Documents "A/6316" and "A/44/49."

[16] Adult Time for Adult Crimes: Life without Parole for Juvenile Killers and Violent Teens, Heritage Foundation report, 2009.

[17] Oakland County Circuit Court Case No. 05-205473-FC.

//Chris Dankovich is a writer, artist, and teacher and has been incarcerated since he was 15. Chris has previously been published in the past four annual PCAP Michigan Review of Prisoner Creative Writing, The Harvard Educational Review's book Disrupting the School-to-Prison Pipeline, and FENCE Magazine, and he recently won second place in PEN American Center's annual prison writing contest.

An earlier version of Dankovich's essay The Atrocity of Sunsets: The Death of Childhood in Michigan appeared in the publication Minutes Before Six on November 13, 2014.