The Introduction of the Byline

In praise of Renata Adler’s fiction and journalism, and against Tom Wolfe and the celebrity reporters of “New Journalism.”

//phil christman

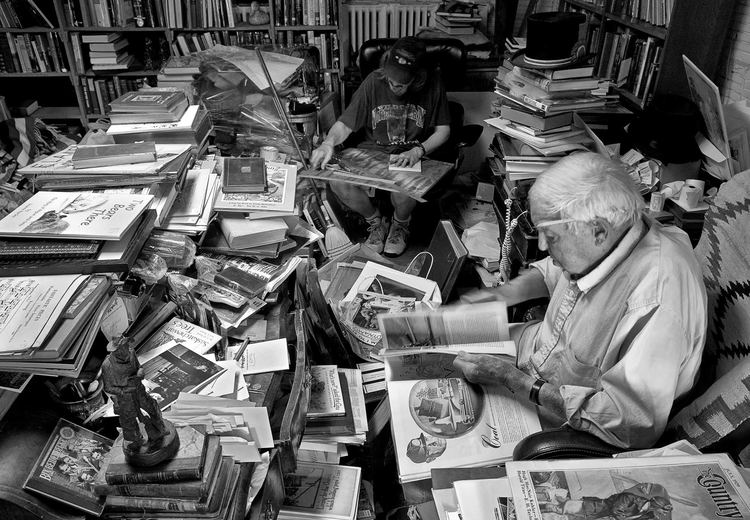

© 2015 Marc Perlish, "Untitled"

A decade and a half ago, when I graduated from college, New Journalism — no longer new, never exactly journalism — was still an inescapable influence on the type of earnest, self-serious young man I was: the Person Who Wants to Write. (You said “want to write” both because writing was holy, not quite approachable, needed a slight remove from that sordid subject I, and because you hadn’t written much.) By “New Journalism” I mean not just longform journalism, or journalism that allows some element of the personal (ultimately, what isn’t personal?), but the highly performative, watch-me-watching-events style pioneered by writers like Norman Mailer and Hunter S. Thompson, and most of all, Tom Wolfe — who was at that time enjoying a moment in the sun. No fewer than four pieces in Wolfe’s 2000 collection Hooking Up either attacked or celebrated his triumph over the soberer style of longform journalism once practiced by The New Yorker and its writers, including one I’d barely heard of: Renata Adler. Like most people under thirty who knew of her at all, I knew her only for “House Critic,” a celebrated 1980 takedown of the film critic Pauline Kael, whom Adler described as “jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption, worthless.”

Times change, as people say — meaning, of course, the opposite, that time yammers on and everything else changes. Tom Wolfe is someone I generally think about only when I scan the bookshelves at a Goodwill. And Renata Adler, out-of-print for most of the 2000s, has since become an inescapable influence. In 2013, NYRB Classics reissued her short, intense, apparently plotless novels Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1983) to nearly unanimous praise. Much of this praise has focused on the sui generis quality of these books, prose collages hard to place in terms of literary history — they are too warmhearted to really remind one of the most obvious possible ancestor, the French antinovel. (One of my favorite Adler aphorisms: “‘Self-pity’ is just sadness, I think, in the pejorative.”) Since the past isn’t that much help, critics have tried to make sense of Adler by assimilating her to the future, calling the books “blog-like” or comparing her jittery narrative voice to the scrambled inner monologue of the multitasker with a smartphone. But this won’t really work either: though the structures of both books suggest an addled mind, their intense, absorbed descriptions do not; again and again, Adler anatomizes, with withering accuracy, social and cultural experiences that we simply no longer sit still for. Take what may be my favorite sentence in either novel, which occurs as the narrator of Speedboat, Jen Fein, is watching TV: “A hideous family pledged itself to margarine.” I laughed long and hard at this, with its efficiency (pledged itself) and accuracy (hideous conveys a shade of meaning you wouldn’t get from terrible or unappealing — you picture people with slightly exaggerated, children’s-book features, which is just right for this kind of commercial). But today Jen Fein would fast-forward. She’d check her phone. She’d have AdBlock installed on her laptop. Nor, more importantly, is the moral vision of the novels ours. Jen Fein says, at one point, with what I suspect is intentional, self-mocking self-importance: “The radical intelligence in the moderate position is the only place where the center holds.” She also says, as if with a little shrug of surprise: “To promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity — I believe all that.” A few sentences later: “I think a high tone of moral indignation, used too often, is an ugly thing.” Left Twitter has many virtues, chief among them its accessibility to voices less privileged than Jen Fein’s, but “a high tone of moral indignation” pretty much exhausts its list of tones.

Readers wishing to piece together Adler’s sources and trajectories are hereby advised to turn to Adler’s nonfiction, collected (with some jarring omissions) in After the Tall Timber (2015) — a book that is jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and (nearly) without interruption, awesome. It is also strikingly like an Adler novel. You could reverse-engineer passages of her fiction simply by taking a piece of her journalism and re-describing events at a slightly higher level of vagueness, taking out a few proper nouns. Take another famous passage from Speedboat, in which Jen Fein tells us: “Intelligent people, caught at anything, denied it. Faced with evidence of having denied it falsely, people said they had not done it and had not lied about it, and didn’t remember it, but if they had done it or lied about it, they would have done it and misspoken themselves about it in an interest so much higher as to alter the nature of doing and lying altogether. It was in the interest of absolutely nobody to get to the bottom of anything whatever.” Add proper names to this and you’d have any number of pages of After the Tall Timber. One passage, in particular, turns up verbatim in both bodies of work — and it is a passage that turns on precisely this question of when to give, and when not to give, the proper noun. From Pitch Dark’s narrator, Kate Ennis:

“The turning point at the paper, as it happened, was the introduction of the byline. There had always been bylines, of course, but only on rare stories and those of the highest importance. Sometime in the seventies the paper began to put bylines on nearly all stories, by everyone. No one could have predicted where this would take us. It seemed, at first, a step in the direction of truth, of frankness. Part of every story had always been, after all, says who? But the outcome, in retrospect, was this. From anonymous reporters quoting, as a matter of the highest professionalism and with only the rarest exceptions, from named and specific sources, we moved gradually, then rapidly, to the reverse: named reporters, with famous bylines, quoting persons, sources, who remained anonymous. There were several results. The reporter himself, with his celebrity, his byline, became in many cases the most powerful character, politically and otherwise, in his own story. The ‘sources’ lapsed, became sometimes highly placed officials floating as facts rumors to which, like pollsters, they wanted to test a reaction, sometimes disenchanted employees or rivals, trying to exact a revenge, or undermine a policy, or gain an advantage, sometimes ‘composites,’ a euphemism for a more or less fictional character introduced for some purpose of the reporter’s own; finally, perhaps, inevitably, absolute fictions.”

When you read it in Pitch Dark, you take this passage as hyperbole, but then it turns up again in Timber — not as fiction, but as the epigraph to a long takedown of the Times and Post in the early George W. Bush era. Adler expands on it only by adding proper names. “The paper” is the Washington Post, the celebrity reporters are Woodward and Bernstein, and the “composite” is the most famous anonymous source in all of American journalism:

“The implausibility of the saga of Deep Throat has been frequently pointed out. Virtually every element of the story — the all-night séances in garages; the signals conveyed by moved flowerpots on windowsills and drawings of clocks in newspapers; the notes left by prearrangement on ledges and pipes in those garages; the unidiomatic and essentially uninformative speech — has been demolished. Apart from its inherent impractibilities, for a man requiring secrecy and fearing for his life and the reporter’s, the strategy seems less like tradecraft than a series of attention-getting mechanisms. This is by no means to deny that Woodward and Bernstein had ‘sources,’ some but far from all of whom preferred to remain anonymous. From the evidence in the book they include at least Fred Buzhardt, Hugh Sloan, John Sears, Mark Felt and other FBI agents, Leonard Garment, and, perhaps above all, the ubiquitous and not infrequently treacherous Alexander Haig.”

Whether or not you buy her argument about Deep Throat — the source credited in Woodward and Bernstein’s All the President’s Men (but only in the book’s second draft) with the leaks that brought down Richard Nixon — the larger story she tells, about the transformation of American journalism into a corrupt cult of celebrity, is hard to resist; Kate Ennis appears, more and more, to be speaking the naked truth.

What After the Tall Timber makes clear is Adler’s real subject, for decades, has been the corruption of institutions devoted to scrupulous analysis and criticism of culture and history by celebrity culture: by the enshrinement of reporter, commentator, or critic, as star. All our critics, she says in effect, have become house critics, speaking from, and for, their own celebrity, in service to a brand name. The proper noun corrupts.

She registers such concerns as early as the first sentence of her first book, A Year in the Dark (1969), writing of “the peculiar experience it always is to write in one’s own name something that is never exactly what one would have wanted to say.” In one’s own name. By the end of the page, she has disclaimed professional criticism as a “way of life” — which perhaps explains why A Year in the Dark, a book of her film criticism for the New York Times, commemorated a gig that she had already quit. In the intro, which also appears in Timber, she gives a brief summary of her career to that point. Originally hired by the New Yorker as a book critic, she moved into reporting, wanting “very much to be there and to be accurate” about “Selma, Harlem, Mississippi, the New Left, group therapy, pop music, the Sunset Strip, Vietnam, the Six-Day War.” And then, we get this:

“I particularly detested, and detest, the ‘new journalism,’ which began, I think, as a corruption of a form which originated in The New Yorker itself. After a genuine, innovating tradition of great New Yorker reporters (A. J. Liebling, Joseph Mitchell, St. Clair McKelway, Lillian Ross, Wolcott Gibbs) who imparted to events a form and a personal touch that were truer to the events themselves than short, conventional journalism, determined by the structure of the daily news, had ever been, there sprang up almost everywhere a second growth of reporters, who took up the personal and didn’t give a damn for the events .… The facts dissolved. The writer was everything …. I remember particularly a reporter for the then ‘lively,’ dying Herald Tribune [Tom Wolfe’s old paper—the plot thickens!] who would charge up to people in Alabama with extended hand, introduce himself, and beginning ‘Wouldn’t you say . . .?’ produce an entirely formulated paragraph of his own. Sooner or later somebody tired or agreeable would nod, and the next day’s column — with some intimate colloquialisms and absolute fabrications thrown in — would attribute its quotes and appear, as a piece of the new journalism.”

Tired of reporting, Adler accepts the movie-reviewing gig at the Times, but she struggles, “from the first,” with the “extremely public” nature of a job that she finds “more like a regular, embarrassed, impromptu performance on network television than any conception of writing I had ever had.” She finds that “near strangers were always telling me whether they agreed or disagreed with me. (This usually produced an evening of doubt, with a particular violence of tone in the review of the following day.)” And she becomes a target of studio meddling: “For some reason, ‘the industry’ was continually upset.” One producer attacks her review of Funny Girl, and then tries to kiss her. A year in the dark, it turns out, is enough. The loose trilogy of pieces on sixties activism collected in Toward a Radical Middle (1970), meanwhile — the book that collected her attempts to “be there and be accurate” about the sixties — collectively tell the story of movements that begin focused on issues and end focused on themselves, on the making of picturesque gestures and the striking of dramatic poses. “There just may be no romance,” she writes, in “Radicalism in Decline: The Palmer House,” “in moving forward at the pace that keeping two ideas in one’s head at the same time implies.” These pieces, too, appear in Timber, and they don’t feel nearly as dated as one would wish.

© 2015 Jo Eun Huh, "Island"

But it is in her work from the period 1970-2003 — the long backlash against the sixties — that we see the full implications of her critique. Though her politics are broadly left-of-center (the center, that “radical middle” she once sought, having shifted left during the Reagan years and after), she’s rarely predictable. But again and again, she does return to that notion of the identified, nameable critic and the unnamed source. Her long polemic against Bob Woodward (the mouthpiece for, or creator of, Deep Throat) begins rather mildly, in a review of his now-forgotten 1981 book on the Supreme Court: “The custom of protecting the identity of sources, in daily journalism at least, has become extremely widespread. I happen to believe that, except when actual, identifiable harm would result, to the source or to some other worthy cause or person, that practice can be unprofessional, a serious impediment to journalism of all kinds. It makes stories almost impossible to verify. It suppresses a major element of almost every investigative story: who wanted it known.” The anonymity of Woodward’s sources in this particular book leads to a kind of vagueness, a sense of gossip-within-gossip, that produces something close to anti-information: “The gossip most characteristically takes the form of a declarative sentence about a frame of mind. ‘Burger was furious.’ ‘Harlan was furious.’ ‘Brennan was furious.’ Innumerable paragraphs begin with the information that one Justice or another was ‘furious,’ ‘delighted,’ ‘upset’ … My favorite piece of American judicial history may be the news (page 326) that ‘Marshall’s clerks were miffed.’” (These sorts of formulations are now pretty much unavoidable in American journalism. And in pretty much every case we’d be better off with a quote — who says that this person felt this way?) The chain of transmission gets so muddled, she writes, that the book’s scoops become impossible to believe. A bombshell revelation like “[Chief Justice Warren] Burger vowed to himself that he would grasp the reins of power immediately” never actually explodes: “Since the authors admit that Chief Justice Burger refused all contact with them, it is hard to know how they can write this quite so categorically. Justice Burger may, of course, have confided his vow to someone else, who then anonymously passed on the information that Justice Burger said he had vowed something to himself. But it is precisely the weakness of this kind of journalism that, because there is no way to check almost any of its assertions, the journalists themselves are sooner or later drawn into some piece of irresponsibility or idiocy; and one has to read every one of their assertions, from the most trivial to the most momentous, with the caveat ‘if true.’”

Adler in these pieces proves herself among the indispensable chroniclers of the Nixon years. She fundamentally rewrites the story of Watergate, perhaps still wrongly, but far more convincingly than the textbook version, in which one President’s petty corruption Destroyed Our Trust In Government and Damaged Our Democracy. (As if a default faith in government were anything but inimical to democracy in the first place.) In Adler’s version of the story, the problem with Watergate is not that it engendered but that it so neatly expunged that distrust, focusing all of it one of Nixon’s comparatively minor misdeeds (Adler is convinced, for complicated reasons, that his real crime was accepting bribes from South Vietnamese officials to extend the war), and saddling American journalism with a myth that ironically made for lazier, more passive reporting: “The whole purpose of the ‘anonymous source’ has been precisely reversed. The reason there exists a First Amendment protection for journalists’ confidential sources has always been to permit citizens — the weak, the vulnerable, the isolated — to be heard publicly, without fear of retaliation by the strong — by their employer, for example, or by the forces of government .... Instead, almost every ‘anonymous source’ in the press, in recent years, has been an official of some kind, or a person in the course of a vendetta speaking from a position of power.” When the Times, in 2003, allowed celebrity reporter-warmonger Judith Miller to report the discovery of made-up Iraqi WMD — citing, of course, anonymous sources — it wasn’t, on this reading, a falling-away from the heroic years of Woodward and Bernstein but those years’ outcome.

Worse, this desire for highly-placed nameless oracles — for one’s own personal Deep Throat — leaves journalists vulnerable to “official accusers, in particular the Special Prosecutors and the FBI.” On this topic, Adler writes far more movingly than I’d have thought was possible of Kenneth Starr’s persecution of Monica Lewinsky, whose Constitutional rights were, on Adler’s analysis, violated during her initial detainment. She writes: “[W]hen those powerful institutions are allowed to ‘leak’ — that is, become the press’s ‘anonymous sources’ — the press becomes not an adversary but an instrument of all that is most secret and coercive — in attacks, not infrequently.” Another term for “official accusers” might be “house critics.” Her several pieces on the (constitutionally questionable) Office of Independent Counsel, and its expensive war on the Clinton Administration, feel particularly timely now, as Hillary Clinton mounts another run and some of the same memes return to circulation.

After the Tall Timber is full of this kind of writing, dense with references to Washington controversies from before I was born, or before I was grown, full of names that conjure up the angry mutterings of one’s parents over the newspaper. And yet is fully as readable as the two novels. Adler’s precision, her aphorisms, her icy anger, her willingness to let a story be as densely knotted with cross-references as it needs to be, make her unnerving but irresistible company. Her attacks on personality-heavy journalism seem prescient now, when a vendor of listicles and a rich Tory’s celebrity gossip site are widely presented as the future of news. Even the qualities that may once have made Adler seem rigid and dull (who gets excited about a “radical middle”?) now seem utterly refreshing. In an era of “sponsored posts” and Silicon Valley worship, we hardly need a Tom Wolfe, with his exclamation points, his love of power, his zeal for new products. What appeals now, what surprises now, what seems unusual and sexy and subversive now, is precisely the low-key earnestness, the ironic self-questioning, the anxious fiddling with details of someone really trying to be there, and be accurate.

//Phil Christman is a writer and an Instructor in the English Department Writing Program at University of Michigan. He is also the editor of the Michigan Review of Prisoner Creative Writing.