In Which the Review Reveals All the Gone Girl Spoilers

//philip conklin

(Disclaimer: Though this article will be appearing nearly a month after Gone Girl’s release, I should still say here that this review will contain the dreaded … SPOILERS! As a matter of fact, in my defiance to the Culture of Spoiler Alerts, I will put as many of these spoilers as possible — and there will be many — in the first two paragraphs.)

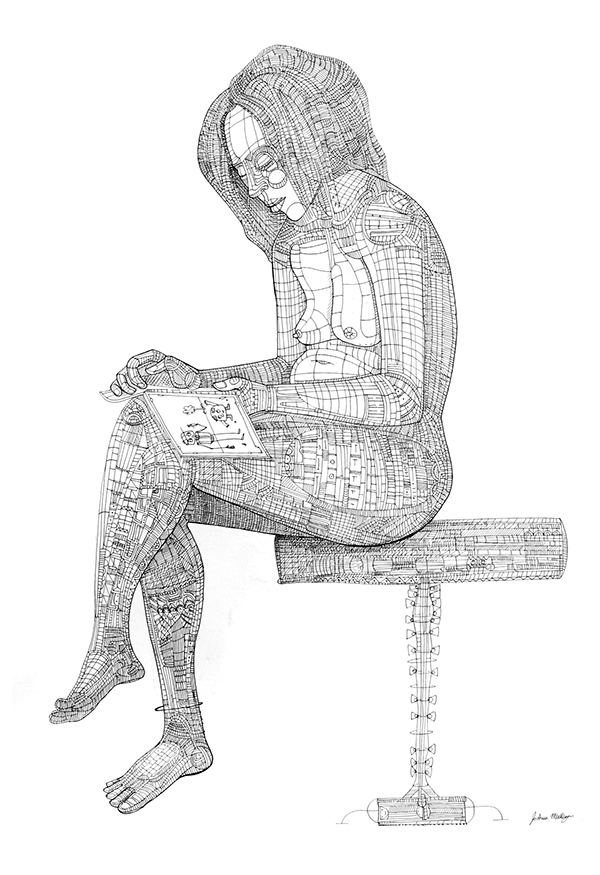

© 2014 Joshua Mulligan, "Watching Cartoons On A Tablet"

Adapted from the outrageously popular novel of the same name, Gone Girl tells the story of Nick and Amy Dunne (Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike), a model couple living a marriage that seems perfect until Amy suddenly disappears under mysterious circumstances. As the police investigation begins, followed by candlelight vigils and national news coverage, the clues point straight to Nick, who finds himself at the business end of a murder investigation, both an actual (police) and a proxy (media) one. But — and here’s the twist — it turns out that Amy has simply absconded, elaborately plotting this whole procedure in order to frame her husband for her murder.

See, Nick is not the good guy he seems, and this relationship is not the rosy conjugal paradise Amy’s voiceover narration would have us believe. When the recession hit and Nick and Amy lost their jobs as magazine writers in New York City, where Amy is from, and moved to North Carthage, Missouri, where Nick is from, away from Amy’s parents and her dwindling trust fund, the marriage went south too. While Nick bought a bar (with Amy’s parents’ money) with his sister and taught classes at the community college, Amy spent long days alone at home with only her books and increasingly psychopathic thoughts as company. Meanwhile, Nick was cheating on Amy with one of his community college students, and the Dunne marriage went from resentful to icy to downright scary.

At its core, Gone Girl is a nightmare of class relations. Amy comes from a wealthy east coast family; her parents wrote a series of hugely popular children’s books called Amazing Amy, based on their daughter. Nick’s family on the other hand is Midwestern and middle-class; divorced parents, aging alcoholic father — we don’t know much about the family’s finances but we do know that they all stayed around the small town of North Carthage, except for the more upwardly mobile Nick, who moved to New York and hung around with a more bourgeois crowd, eventually marrying the poster child of the bourgeoisie.

(But let's talk about spoilers. Gone Girl is a particular case because it was such a widely read book [it has sold over 8.5 million copies], and so the plot is already familiar to so many people — which also turns the faithfulness of the movie’s plot to the book’s an issue in itself, in turn making the plot an even more significant topic of discussion. Even those who haven’t read the book may be familiar with the plot; for example, I knew the major twist of Gone Girl — that Amy framed Nick for her murder — because my mom read the book and had to reveal major plot points in order to explain why she didn’t care for it. It’s possible my knowing this twist contributed to my lack of interest in much of the film. Then again, if a movie’s only point of interest is its plot, then the filmmakers are doing something wrong.

Obviously, someone who wishes to write about films is considerably more invested in how much you can say about them in public. But is the general population really so sensitive to the revelation of plot detail as they’re made out to be? Obviously there is a certain amount of pleasure derived from surprising plot twists, and even more from the development of a well constructed story; but not the sole pleasure a film has to offer. And spoiler alerts are only a very recent phenomenon. As Jonathan Rosenbaum has pointed out, classical literature is riddled with spoilers. Would the chapter titles of Don Quixote be considered spoilers nowadays? Or what about Shakespeare? Maybe we didn’t want to know that -- spoiler alert -- the Shrew gets tamed at the end.)

Much is made in Gone Girl of the conflict and perceived differences between these two poles: urban/rural, wealthy/middle class, intellectual/un-intellectual, duplicitous/honest, sophisticated/simple, wine/beer, and on and on. The two major geographical reference points, New York City and North Carthage, are set in dialectical opposition. The one is a bastion of culture and money, where you meet beautiful people, enjoy your parent’s trust fund, and have an interesting and modern job like magazine writing; the other is a homey, mostly rundown place where there are bars called The Bar (un-ironically, I might add — this ain’t Brooklyn), where everybody knows your name, and where the neighbor (Casey Wilson) is a perpetually pregnant stay-at-home doofus who is never seen without a stroller and takes the word of daytime TV hosts as gospel.

It's this conflict that’s at the root of Nick and Amy's marital problems. When they're both laid off, they know they can rely on Amy’s wealthy parents and her trust fund to get by. But when her parents need to take a cool million out of the trust fund for themselves (it’s their money, Amy reminds Nick), problems flare up. Amy gets another job, and Nick winds up sitting on the couch most days in his sweatpants playing video games (how terribly boorish).

When Nick’s mother gets cancer, Nick decides they should move back to Missouri to help her (Amy doesn’t mind, she just wishes he would’ve asked her). It’s when they’re back in North Carthage that it really hits the fan. Nick, native son, fits in like a glove, but Amy — the haughty, Harvard-educated, East Coast princess — is out of place. She stays home all day reading and plotting, while Nick is hangin’ out and watching sports with high school buds and sleeping with his 19-year-old creative writing student.

This conflict is even inscribed in the way these actors look and move. Affleck has the lumbering thickness of a high school quarterback on the precipice of middle-aged flabbiness (that villainous chin may soon have company), with an easy small-town charm and naïveté about people and the world. Pike, on the other hand, is icy cold, sleek, thin, and fashionable, with the movements of a dancer, always immaculately put together and one step ahead of the game.

© 2014 Justin Kingsley Bean, "Display Shift"

(Spoiler alerts are made possible by and exist because of the Internet. A google search for "Gone Girl spoilers" reveals articles that consider the subject or at least warn about them in seemingly every publication that has written about the movie, and many websites with sections entirely devoted to discussing them: reddit, the A.V. Club, and Screen Rant, to name a few. See, with so many more avenues to watch, discuss, and generally be aware of films — videos, articles, memes, social media, podcasts — there are more ways to hear about some movie that you would rather not hear about, more fans with whom you can predict or complain about juicy endings, etc. Compounded with that, more films are available to watch than ever, meaning that every film ever made is still on the table in terms of spoilers; just because Citizen Kane came out over 70 years ago doesn't mean that everyone's not going to get around to it at some point, so it's best to keep mum. The Internet also entails immediacy and universality; the second any bit of information about a film is available to one person, it’s available to everyone.

But although spoilers now accost us from all sides and at all times, the prominence of spoiler alerts is completely overblown. The studios likely play a role in this process as well. It’s in their interest not only to preserve the mystique for possible ticket-buyers, but also to suggest that there’s a mystique at all. A movie with a plot point so juicy people have to stop themselves from talking about it in public holds more appeal to the average moviegoer than one without. A film that’s talked about, even if what’s talked about is mostly that we’d better not say too much about it, gets more press than one that’s not talked about.

All this spoiler hullabaloo is also a pretty major contradiction in a movie industry that relies almost entirely on sequels, remakes, and films based on previously released material. It would seem that in this landscape the last thing that would distinguish movies from one another would be their plot, the only element of a film that is often already known to so many people — in this case, around 8.5 million people. On the other hand, Hollywood movies tend to sort of run together, making plot an important distinguishing factor between movies that are identical in style and substance. Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice will probably look and feel a lot like Man of Steel which looked and felt a lot like The Amazing Spider-Man [and for that matter The Amazing Spider-Man 2]; but despite these similarities their plots will probably vary quite a bit.

In other words, spoilers are essential in this environment, where audiences need something to keep them interested in the endless traffic jam of very nearly indistinguishable studio shlock, and studios have to keep people coming back to the theater — and more importantly keep watching TV, subscribing to pay-TV, and buying DVDs. As long as there are new plot points, twists, turns, and surprises, we feel compelled to keep watching and buying.)

A lot has been said about how Gone Girl depicts gender, about its relative levels of feminism and misogyny, about its conception of marriage and the role of women in society. While there’s certainly a lot to talk about in that regard, what Gone Girl has to say has much more to do with this urban/rural, upper-class/middle-class polarity than with any sort of gender politics. Look at the other women in the film: Margo (Carrie Coon), Nick’s twin, is a tomboy type who has more in common with her brother than with Amy, whom she detests; Detective Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens) is a smart, cynical police officer with a southern accent and a casually professional demeanor. The only female character similar at all to Amy is, tellingly, her mother.

Our fear of Amy, and her power, derives from an anxiety about the power of modern, urban women in general. This is a trope that exists in film at least as far back as 1921, in FW Murnau’s Phantom, and has run through the movies ever since. In film noir, this type of character would be called a femme fatale. For a character like this, her modernity and urbanity are tied up with an intense sexuality, which is tied up with her power over men, which is the reason behind both the attraction and fear men feel for her. Amy’s sexuality is her tool for the seduction of men, and also the means by which she destroys them, whether it be by blackmail (as when she lies about being raped by a former boyfriend) or murder (as when she slits the throat of another former boyfriend during sex) or anything else. Amy Dunne appears on the surface almost the perfect woman — beautiful, intelligent, creative, rich, and classy. But Gone Girl shows us that the flip side of this is a capacity for homicidal, sociopathic behavior. In other words, the sexier, smarter, and more powerful a woman is, the greater her capacity for bitchiness.

Sure, Gone Girl also has things to say about the news media and social media (mainly that they exist), but the film’s politics, which have been so fervently discussed, are rooted in this anxiety about the clash between the modern and the traditional, the urban and the rural. It’s a trope that’s been around since the early part of the 20th century, and though I’m not sure Gone Girl has anything new to say about it, it has the right amount of psychological and arty heaviness to keep people talking about it seriously at least until the Oscars are over.

(What bothers me most about spoiler alerts is that I care less about the plot of a movie than almost everything else about it. What enjoyment I got from Gone Girl came not from the revelation of surprising plot information, but from the atmosphere that David Fincher and company created, an atmosphere of suburban decay — both physical and moral. The house Amy and Nick live in is sleekly modern but gray and empty; like their marriage, there's darkness behind its pretty façade. Why is this not considered a spoiler, but saying that Amy framed Nick for her murder is? Is it a spoiler to describe Affleck as "lumbering" or Pike as "sleek"? Is it a spoiler to meticulously delineate a class conflict at the heart of the film?

To me, these "spoilers" are as significant as knowing that Nick has been cheating on Amy or that at the end of the film Amy is pregnant. Film is a narrative art form, but how the narrative is told is, to me, much more important than what the narrative tells. There's certainly something to be said for plot, for a story beautifully told; but even then the pleasure comes from the process, not from the information itself. Character development, relationship development, drama -- these are all things that take shape through a communication between the film and the audience.

Ideally I like seeing a film without knowing plot details, or any other details, beforehand, since it makes the discoveries fresher. But even if I'd known every detail of Gone Girl's plot before seeing it, if it had been an intricately constructed and sensitively told story, I expect I would have still found considerable enjoyment in it [as it stands I only found occasional enjoyment]. And certainly no spoilers could ruin a film's cinematography, direction, or acting. The aspects of movies that, I think, have the most to offer are experiential; they can only be transmitted by watching the film and can’t be ruined by any explanation, no matter how long-winded and analytical. Lucky for you.)

//Philip Conklin is a co-founder of The Periphery.