Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s TV Dreams

A short history of the eccentric founder of the activist group Jazz and People’s Movement of the 1970s and his dream to bring Black jazz musicians to popular television.

//John G. Rodwan, Jr.

A sightless man with multiple saxophones as well as other horns, flutes, and, literally, bells and whistles hanging from his neck, a person whose circular breathing technique allowed him to hold a note for several minutes at a time and play two or three instruments simultaneously and continually and well for twenty or more minutes — such an individual might seem ideally suited for television. Even if the musicianship didn’t resonate with viewers, the novelty of someone singing through one flute and playing another with his nose should certainly have held their attention.

Yet Rahsaan Roland Kirk had to fight his way onto the airwaves, and when he finally did appear on one of the biggest TV shows of his day, he made sure not only to be noticed but to make a point. Though aware, and deeply annoyed, that his peculiar showmanship distracted some from his artistry and invited his dismissal as a sideshow, Kirk also resented the tendency of the media and art organizations to slight black artists generally and jazz musicians specifically. It would probably be overstating the case to say Kirk’s efforts with the Jazz and People’s Movement (JPM) in the 1970s led directly, a couple decades later, to the world in which esteemed jazz musicians could work as band leaders on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno (as saxophonist Branford Marsalis did from 1992 to 1995 and as guitarist Kevin Eubanks did from 1995 to 2010). Yet it would not be going too far to say that Kirk and his outspoken associates extended the tradition of black musicians joining struggles for equality and justice — and that they did make an impact. The debt may be impossible to quantify with precision, but artists in an era when black performers are routinely featured on television owe something to predecessors, like Kirk, who strove to make that a reality when the situation was very different.

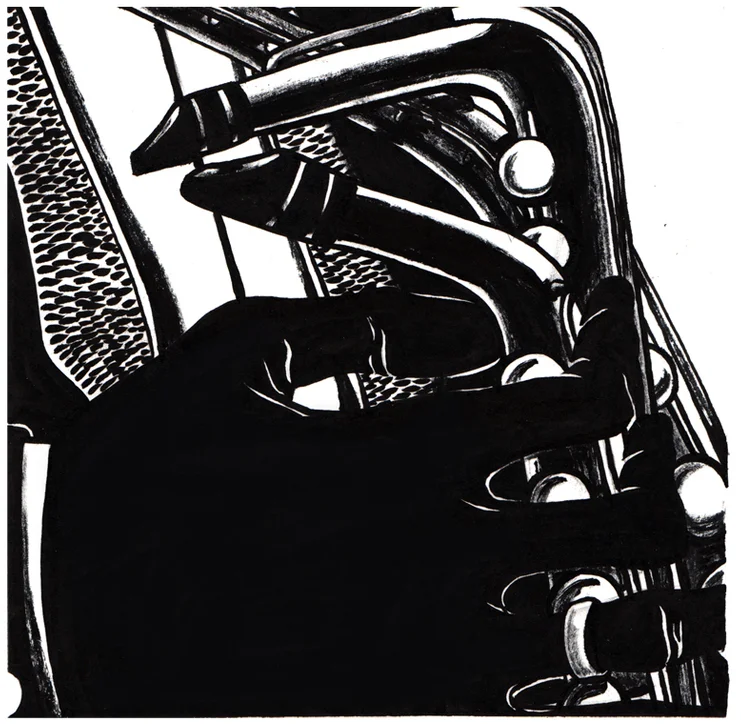

© 2015 Brach Goodman, "Jazz Hands"

Kirk, who was born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1935, lost his vision during infancy but disliked the word blind; he insisted he simply saw differently than others. He conflates sight with sound in the title of 1975’s The Case of the 3 Sided Dream in Audio Color. Kirk also claimed to get many of his ideas, such as deploying numerous musical instruments in pursuit of his artistic vision, from his dreams. In addition to his battery of tenor saxophone, clarinet, oboe, flutes and whistles, Kirk equipped himself with customized versions of obscure instruments, such as the stritch (a modified straight alto saxophone) and the manzello (derived from the straight soprano sax).

Such dreams and the sounds they inspired might make Kirk seem odd or willfully eccentric to someone unfamiliar with his work. For all his experimentation, however, Kirk believed himself to be firmly rooted in jazz tradition and highly respectful of predecessors like the saxophonists Sidney Bechet and Don Byas, for whom he composed tributes. While reverent of what music came before him, Kirk remained open to contemporary sounds. He re-imagined Stevie Wonder’s “My Cherie Amour” as well as Dionne Warwick’s “I Say a Little Prayer” and “Walk on By,” and Bill Withers’s “Ain’t No Sunshine.” He also made some fairly commercial music when working with other band leaders. Thus, many moviegoers have heard Kirk play even if they don’t know it. He played the flute on the 1962 Quincy Jones track “Soul Bossa Nova,” which thirty five years later became the theme for the Mike Myers comedy Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery.

As part of his habit of drawing on the past while moving forward, Kirk fused his music with activism. Jazz already had a history of involvement with the civil rights movement, as crystallized in recordings like singer Billie Holiday’s rendition of “Strange Fruit,” drummer Max Roach’s We Insist! Freedom Now Suite, saxophonist Sonny Rollins’s Freedom Suite, Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam,” and bassist Charles Mingus’s “Original Faubus Fables” — a song written in response to Arkansas’s governor attempting to block school desegregation — and “Haitian Fight Song.” As Mingus told music writer Nat Hentoff, “Haitian Fight Song” could have been called “Afro-American Fight Song.” For the fiery tune, Mingus drew on the church music of his youth as well as his sadness over persecution. He couldn’t play it right, he said, without “thinking about prejudice and hate.”

The intersection of jazz and activism extended beyond penning protest songs. In 1960, for instance, Mingus organized an alternative to the Newport Jazz Festival, which George Wein began running in 1954. Mingus objected to Wein’s booking of more commercial rock and folk acts and slotting jazz artists in less prestigious afternoon portions of the schedule. Mingus was particularly perturbed to discover that swing-bandleader Benny Goodman was offered $5,000 to appear when he was offered just $700. He couldn’t help but notice that the more “mainstream” artists collecting the bigger checks just happened to be white.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Kirk took inspiration directly from Mingus’s counter-festival when starting the Jazz and People’s Movement. This time, instead of protesting inequality and insults at jazz festivals, Kirk, trumpeter Lee Morgan, and other activists protested the invisibility of jazz musicians on television. Participants, up to 80 at a time, disrupted Dick Cavett’s, Johnny Carson’s, and Merv Griffin’s talk shows by entering studios as audience members and then blowing whistles, holding up signs denouncing their exclusion from broadcasts, and interfering with the shows’ tight schedules. Morgan claimed the only reason representatives from these shows met with the JPM members to discuss their demands was because he, Kirk, and the others showed up with their whistles and placards — and kept showing up.

In January 1971, producers of The Ed Sullivan Show, having received advance notice of a planned disruption, decided to circumvent it by inviting Kirk to appear on the program. Sullivan’s show had already famously showcased the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Elvis Presley — precisely the sort of white acts that the JPM organizers believed (correctly) had displaced jazz even while drawing from the musical well dug by black musicians. While obviously taking cues from the blues, such performers helped push jazz to the periphery of popular imagination. By the early 1970s, bands like the Stones were filling arenas, while only the best known jazz artists, such as Miles Davis, could fill concert halls.

In the weeks preceding Kirk’s episode, musicians on the show included Tony Bennett, Gary Puckett, O.C. Smith (singing “What the World Needs Now”), and Bobbie Gentry and the Goose Creek Symphony. The plan was for Kirk, accompanied by fellow saxophonist Archie Shepp, Mingus, and drummer Roy Haynes, to perform “My Cherie Amour.” Kirk associate Mark Davis, who help arrange the booking, wondered why Kirk would assemble such a band of luminaries, some of whom (Mingus and Shepp) were very outspoken about civil rights, to play an anodyne pop tune. As it turned out, Kirk had an alternate plan. Instead of playing the Stevie Wonder hit, Kirk performed “Haitian Fight Song,” Mingus’s wordless lament over the state of race relations. (The performance appears in The Case of the Three Sided Dream, a documentary directed by Adam Kahan that screened at film festivals in 2014. According to Kahan, it showed Kirk was “into knocking down obstacles.”)

As JPM’s name indicates, the initiative was about both jazz as well as the people performing it. (“Look, we’re talking about jazz,” Morgan, who died about a year after the broadcast, stressed when talking about the JPM in his last interview.) At a moment when rock and roll was ascendant, Kirk extended the group’s effort not only by appearing on the program but by playing a jazz song with an aggressive edge instead of something pretty from another genre. Some jazz journalists, such as Dan Morgenstern, believed Kirk might have more effectively made the case for jazz on TV if he had played a more accessible song.

But sneaking around obstacles wasn’t Kirk’s method. What Kirk did was an uncompromising way of insisting that the music still mattered. If on The Ed Sullivan Show Kirk displayed his anger, he also retained his sense of humor. After the program went off the air later in the year, someone congratulated Kirk for his appearance on the show. “Thanks, but don’t blame me ’cause it went off the TV,” Kirk replied. “It wasn’t my fault!”

A couple of months after the TV gig, the Jazz and People’s Movement picketed outside the offices of the Guggenheim Foundation; not long after, Mingus received a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship (only the seventh jazz composer to win one up to that time).

As Kirk and his movement allies knew, talented black performers being overlooked is a persistent problem, and sometimes the solution is to make noise about it. Decades after Kirk’s death in 1977, the tactic he and they used in the bid for recognition and fair treatment — drawing attention to the problem by various means and compelling those in power to respond — continues to be used in the ongoing struggle for racial equality. The man who saw differently wanted to be seen, and he made sure he was.

//John G. Rodwan, Jr., is the author of Holidays & Others Disasters (Humanist Press, 2013) and Fighters & Writers (Mongrel Empire Press, 2010) and the co-author of Detroit Is: An Essay in Photographs (KMW Studio, forthcoming). His writing has appeared in numerous magazines, newspapers and journals as well as A Detroit Anthology (Rust Belt Chic Press, 2014). He lives in Detroit.