First night at the normal school

//lhea j. love

It was bullshit.

We walked down the stairs of the abandoned church into a room lit only by candles. And before the toe of our boots hit the bottom stair, we tumbled onto our faces. It must have been pillowcases, black or navy, thrown over our heads until they hugged the top of our shoulders. We were pulled from the safety of the floor to a standing position by the grasp of unseen grips. The thin t-shirts we wore, probably made and inspected by children half our ages but under better conditions, were ripped as they dragged us across the room and shoving us backwards until our heads hit the wall.

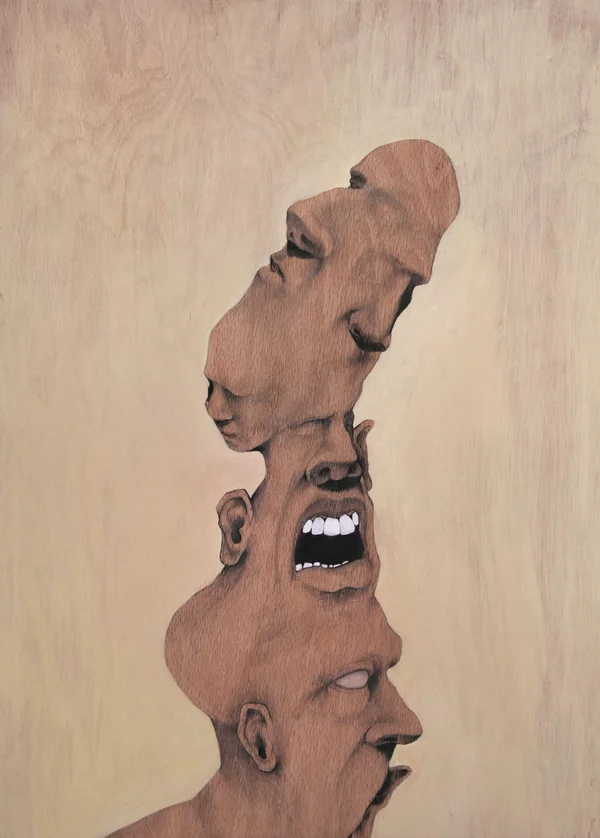

© 2014 Eli Stevick, "Devin"

We would have sulked in pain if we were not distracted by the voices of our Big Brothers. The second blind fold came, perhaps a t-shirt or towel or linen this time, wrapped horizontally atop each of our noses, over our eyes. As if an act of charity, we felt a blade cut a line between our noses and mouths. They pat us on our backs, on our shoulders, before the games began.

But ‘game’ is a misnomer, bullshit is a more accurate word.

Normal became silence and grunts and yelling, pain. We bowed and kneeled and stooped, apologizing. We were sorry that we talked wrong, dressed wrong, looked wrong. Really, we were apologizing for who we were. We really did want to be men.

After sundown, before daybreak, we arrived after classes and after studies. We took an oath of celibacy — no women, and honestly, no men. We arrived without smiles and without laughter. We arrived with the legacy of a century.

We learned everything and nothing at all. We learned names without biographies and biographies without context. We memorized more with each other than we would for all of our collegiate courses combined. We learned to learn without sleeping and sleep without lying down. We ate our own spit, each others saliva and, probably, a bit of blood. We drank sweat, swallowed vomit, ate feces and forgot by the next day.

The first thing they did was laugh. Blindfolded, we heard the chortles of grown men more than we heard our own breath.

We carried a stench with us. We each smelled of sweat and Old Spice or sweat and Degree or sweat and True Religion. But, we all smell of sweat.

We stood up for hours, helplessly. We stood until our soles ached. When we lay, we did push ups. When we sat, we did crunches. We were never still. There was always someone watching; there was always someone screaming; there was always someone to point out what we did wrong.

We were wrong for having different clothes — the colors matched, but they were not exact; we were wrong not speaking in unison — individually we knew what to say, but we could not speak together; we were wrong for not moving in unison — we were only as strong as our weakest brother. We learned that our hundred push ups or pull ups or sit ups or chin ups mattered not, if our brother could only do two. We only did what all of us could do.

What we could all do was never enough.

Normal became hyperventilation and inhalers tied around our necks. Normal was anxiety and panic attacks and rashes and hives. We were used to the violence of laughter but we were not used to failing.

We became failures. We could not please the laughers; we could not pacify our professors; and ultimately, our girlfriends left us all. We could not bemuse each other or justify our own existence. We became depressed and suicidal and bitter and enraged.

We changed. We saw the world in negative reinforcements. We understood how Dr. King and Rev. Jackson and Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young and Huey P. Newton were stronger activists because of this. We saw institutions of power that wanted us to be Black and powerless and uneducated and poor when we only wanted to be Black. We thought that the KKK, FBI or CIA didn’t have nothing on our Big Brothers. We thought our families meant well but could not understand our transition from boys to men, our ritual of passage from cogs to revolutionaries, especially our mothers.

© 2014 Tarah Douglas

When they removed our blindfolds, there were more of them than us. They were not smiling; as much as they had laughed, they looked disgusted that we were the chosen.

We had felt the unfinished, concrete floor beneath our feet, our backs, our faces; but, now we could see it. There were cobwebs in each corner we were forced into and, if we looked hard enough, the spiders to go with them. Maybe decades ago normal Christians fellowshipped here; but, now there was no electricity, no water, and no heat. Now, there were only us seven — my six brothers and I — surrounded by upperclassmen and alumni, by doctors and lawyers, by businessmen and artists. Now, there were only us fools, asking to be made men.

We looked at each other and wondered if we were changed men. We shared a vulnerability only men in this room could understand. We saw each other’s faults. Our feet were funny, our legs too and when they stripped us of our pants — our penises were funny: too narrow or too bent or too black or too soft.

We were grabbed without fondle — kicked, slapped, punched, shoved until we stumbled over each other. We were walked on and dragged about; we were lifted up and slammed down until we decided to protect each other from the physical danger of the laughter that lingered too long.

We found ourselves drooling and groveling or pleading and praying, on our knees or on our backs, until we shed blood.

Normal became scarred backs and split buttocks.

Normal became permanent bruises and broken bones.

Normal was our lies.

We learned that the walls could not save us, the ceiling was too far to reach and the floor was a trap for the fallen. We had each other’s backs. Once we found a line too tight to be questioned, we never broke our links. We stood and sat; sleeping, studying and eating in our line. In line, we prayed for our hearts, our kidneys, our endurance and our grades. We prayed that we would not die trying although each of us thought that it was worth it. We faced the world, or at least the laughter of the men who doubted us, and linking elbows, placed our left fist diagonally across our backs and our right fist across our hearts, pledging allegiance to the only true God our Savior first, then to each other.

//Lhea J. Love is the author of two poetry books. She is currently finishing her first novel. She lives in Detroit with her daughter Harper Lee.